-40%

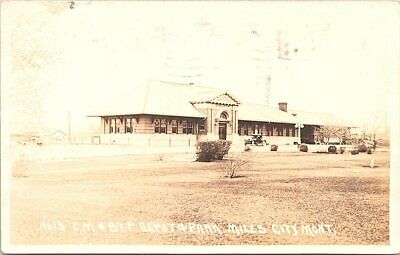

Miles City Montana RPPC Railroad Depot 1920

$ 17.41

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Real Photo Post Card. Please see both images above for condition.Thanks for looking!

Gardiner, Montana—End of the Line

A Town’s Raw Mountain Mood at Yellowstone’s North Entrance

BY LISA BARIL

During the summer of 1911, Dorothy Pardo boarded a south-bound locomotive at the red brick train depot in Livingston, Montana. She was destined for the small mountain town of Gardiner at Yellowstone National Park’s doorstep. During the leisurely two-hour ride through Paradise Valley, Dorothy leaned out her window as far as she dared, taking in views of the mountains that lay before her “like soft, undu-lating folds of velvet…but so rugged, so dauntless, so free.”

The train whistled through, to Dorothy’s eye, “a few unattractive settlements” along the way including one at Emigrant, where some passengers set out for a dude ranch adventure. Others chose to visit Chico Hot Springs at the base of 10,960 foot Emigrant Peak. Although Emigrant depot has long since disappeared with the railroad, the Old Saloon continues to quench Montanan’s undying thirst for whiskey and fellowship.

At the head of Paradise Valley, Dorothy’s train squeezed through Yankee Jim Canyon before entering the parched Gardiner basin in the shadow of the Absaroka-Beartooth and Madison ranges. Gardiner, a small, but bustling western town nestled at the confluence of the Gardner and Yellowstone Rivers, was the last stop along the Northern Pacific Railroad’s Park Branch.

When Dorothy arrived she called Gardiner “a typical western town” finding dusty streets lined with tightly knit saloons, hotels, and shops. Their false fronts giving the appearance of permanence in uncertain times. After a brief stop in Yellowstone’s first gateway community, Dorothy embarked on a six-day journey through Wonderland—an appellation applied to Yellowstone by the Northern Pacific Railroad to promote tourism to the region.

A Veritable Shantyville

Gardiner is named for Johnson Gardner, a trapper who collected beaver and muskrat skins along his namesake river in Yellowstone during the 1830s, long before the area was designated a park. Gardner, an unsavory character by some accounts, reputedly absconded with 700 skins from the Hudson’s Bay Company during his early exploits.

Gardner was long forgotten until Jim Bridger, a fellow trapper and member of the Washburn Expedition, revived his name in 1870, applying it to the river nearby. Bridger’s thick Virginian drawl led to the insertion of the “i” in today’s spelling.

For the next 30 years Gardiner was left to the ebb and flow of gold seekers and explorers until James McCartney, a carpenter from New York, settled a claim at the mouth of the Gardner River in 1879, becoming Gardiner’s first permanent resident. McCartney’s claim in Gardiner came on the heels of his forced exodus from Mammoth Hot Springs as tensions with Yellowstone’s Superintendent grew over his illegal claim in the newly established national park.

Recreating what he lost in Mammoth, McCartney built a small hotel, shop, and saloon along the west end of present day Park Street in Gardiner where the beer was said to be disappointing. McCartney’s new claim was also inside the park, although no one knew it at the time since Yellowstone’s boundaries were imprecisely drawn. The following year McCartney added a post office making Gardiner official and McCartney its unofficial mayor.

The youthful town of Gardiner began to grow and by 1883 boasted “…six restaurants, five general stores, two hardware stores, two fruit stands, two barber shops, a newsstand, a billiard hall, two dance halls, four houses of ill repute, a blacksmith shop, twenty-one saloons, and a milkman,” remarked one visitor.

The year 1883 nearly burgeoned for this nascent community. A gold claim was discovered by Buckskin Jim Cutler (so named for the buckskin jacket he wore in an easterner’s misguided notion of western garb). The same year, the Northern Pacific Railroad announced that Gardiner would be the southern terminus of the Park Branch and began promoting Yellowstone as a travel destination.

But “Buckskin” Jim Cutler’s claim sat squarely on the proposed Park Branch terminus. Cutler dug his heels in. McCartney was not happy and he and Cutler feuded over the claim and the future of Gardiner. The Northern Pacific Railroad, hoping to settle with Cutler, began laying tracks, but making little headway with “the tough old codger,” terminated the line at Cinnabar, three miles north of Gardiner.

It was a huge blow and one that would hinder Gardiner’s growth for the next 20 years.

One early visitor described Gardiner as “no more than a collection of tents and log huts. A veritable Shantyville, Gardiner City, an ideal squatter town with the rudest houses made of unseasoned boards, with not a few tents mingling with the more pretentious huts, huddled together as though the land was valued by the foot and inch.”

But Gardiner’s residents were proud of their ramshackle town. It wasn’t much, but they’d built it with gnarled hands and fierce determination—people like McCartney, the unofficial mayor, and Billy Shrope who hauled water out of Gardner River selling it for fifty cents a barrel, and John Spiker who provided visitors with lodging at the Cottage Hotel.

Even after a carelessly dropped cigar in Cowell and Lewis’s Saloon (on Park Street) ignited a fire that swallowed 13 houses and 19 businesses in 1889, residents believed in Gardiner’s future enough to rebuild—no easy task without a railroad to ferry much needed supplies.

Gateway to Fairyland

In 1902, Gardiner’s residents breathed a collective sigh of relief when the Northern Pacific Railroad extended the tracks those last three miles. And with their next breath residents set to work on shedding the image that “there was nothing attractive [in Gardiner] nor curious enough to make [one] long to tarry,” according to one early visitor.

They began with the Roosevelt Arch—an idea conceived by Hiram Chittenden, an officer for the Corps of Engineers in charge of road design and construction in Yellowstone. In one of Gardiner’s proudest moments, nearly 4,000 visitors gathered around the unfinished basalt arch for the laying of the cornerstone by President Theodore Roosevelt on April 24, 1903.

“The flashing swords of the officers, the martial music of the band, and the lusty cheering of the assembled multitude,” admired one reporter, “gave the scene an aspect which would inspire enthusiasm and patriotism in the breast of a cynic.”

Eight years after the cornerstone was laid, Dorothy Pardo, riding beneath the arch in a stage coach, wrote that the arch gives “one the impression of space—breadth, height, and vastness…and one wishes that no others save those who love Nature in all her moods, might ever pass through the massive stone archway marking the entrance to the Nation’s fairyland.”

Four months after the cornerstone was laid, the last rough-hewn log was set upon Gardiner’s new train depot’s stone foundation. The depot was designed by Robert Reamer, famed Yellowstone architect of the Old Faithful Inn. Its rustic character introduced visitors to Gardiner’s authenticity as a real western town, not simply a tourist stop.

Visitors’ first glimpse of Gardiner, after stepping off the depot platform, was of Park Street—the town’s main hub that was built, inadvertently, inside the park boundary so that visitors stumbling out of Tripp and Melloy’s Saloon did so literally into Yellowstone Park.

Park Street bustled with a tailor’s shop, a post office, a restaurant, several saloons, a livery, and most prominent of all, W.A. Hall’s store.

Hall’s sold everything—a claim boldly painted in large white letters on the rust red bricks facing the depot. The faded letters can still be read today though Hall sold his business in 1955.

“If you want it, Hall has it from an ounce to a car load and from a needle to a saw mill,” read an advertisement in a 1903 issue of Gardiner’s Wonderland newspaper. Hall advertised wool blankets made in Big Timber and “Noxall shirts ranging in price from 50 cents up to .75…shoes of the best quality…and groceries.”

At last, Gardiner was beginning to shed its shantyville image.

Building a Community

The railroad transported thousands of passengers to the Gardiner depot during Yellowstone’s brief summer, establishing Gardiner as one of Yellowstone’s most important gateway communities—a title owed to those last three miles of track laid in 1902.

Much like today, residents eked out a living on a seasonal boom and bust cycle where visitors flooded Gardiner’s restaurants and hotels during summer and rolled out on the last trains before winter set in. Gardiner has never been an easy place to live and few, if any, got rich providing for Yellowstone’s visitors.

Gardiner’s winters were long with the population dwindling to a few hundred residents, but dances, operas, and dinners kept resident’s spirits high in the off season. Many of these occasions took place on the second floor of W.A. Hall’s store.

For a few dollars Gardiner’s residents celebrated one Christmas Eve with dinner and music provided by the Cosmopolitan Symphony orchestra from the nearby hamlet of Jardine. Hall’s really did sell everything, including a good time.

The Christmas morning paper that year read “The dance given by the clerks at Hall’s auditorium Christmas Eve was considered by all who attended to be one of the pleasantest affairs of the kind that has taken place in Gardiner this winter.”

As the town grew and visitors increased so did the need for a church, schoolhouse, and community center. Many of these buildings still grace the Gardiner landscape as reminders of the town’s past. The stone and gable roofed church, Gardiner’s first, still provides refuge for residents and the community center stage still comes alive with plays, music, and public meetings.

McCartney’s struggle to make Gardiner into a viable community had been realized.

More Than a Facade

The Park Branch line ran for 53 years peaking in 1925 with more than 17,000 passengers riding the rail to Wonderland, including Dorothy, who returned in 1926, so enamored was she with her first experience fifteen years before.

But the railroad’s heyday began to wane. Trains and horse drawn wagons could not compete with the convenience of the automobile, however unreliable they sometimes were. In 1917 the stage coach, used to take visitors on week-long tours of Yellowstone, became a novelty as automobiles commandeered the roads. And in 1955 the last passenger trains pulled into the Gardiner depot with a group of girl scouts on board.

Over the decades, the thousands of tourists became millions, but despite the increase in visitors, Gardiner has maintained its small town authenticity. It has always been more than the facade of western shop fronts, more than a tourist stop—its raw mountain mood still palpable with or without the railroad

Please check my other auctions for more vintage photos.

Use posted auction images to determine condition.

In most cases, the actual original photos are much clearer than the posted images.

=========

If you have any questions, feel free to email me and I will do my best to answer.